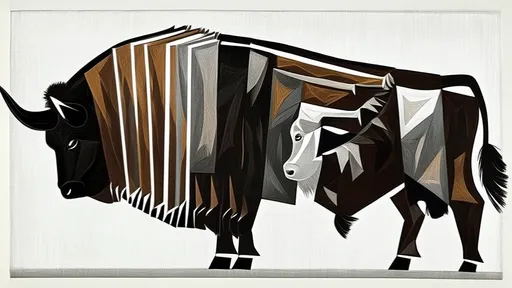

In the labyrinth of contemporary Chinese literature, Wang Xiaobo’s "The Golden Age" stands as a grotesque monument to intellectual rebellion. At its heart lies a peculiar allegory—humanity’s relentless pursuit of freedom through the lens of pigs. This isn’t pastoral symbolism; it’s a bloody-minded satire where barnyard animals become unwilling revolutionaries. Wang’s porcine protagonists don’t oink platitudes about liberty—they rut, defecate, and die with a perverse dignity that shames their human oppressors.

The genius of Wang’s swine metaphor lies in its utter lack of romanticism. These aren’t Orwell’s noble proletarian animals marching toward utopia. When Wang’s pigs break free, they don’t establish animal farm regimes—they simply revel in their messy, ungovernable existence. One memorable scene depicts a fugitive pig copulating vigorously in a cabbage field while Red Guards scream revolutionary slogans nearby. The animal’s raw biological imperative becomes the ultimate rebuttal to ideological purity.

Wang constructs his absurdist universe with the precision of a mad biologist dissecting society’s hypocrisies. His human characters—often hapless intellectuals trapped in Mao-era political campaigns—develop swinish traits through sheer survival instinct. They learn to root through garbage heaps of propaganda for scraps of truth, to wallow in the mud of political theater without drowning. The transformation isn’t metaphorical; Wang’s prose forces readers to smell the stench of real pigsties mingled with the reek of human fear.

What emerges isn’t some trite "be yourself" fable but a radical desecration of all sacred cows. Wang’s pigs achieve freedom not through righteous struggle but through glorious, unrepentant obscenity. In one deliberately offensive passage, a sow gives birth during a political struggle session, her squeals drowning out a party official’s denunciations. The scene’s vulgarity isn’t gratuitous—it’s theological. Wang suggests that true liberation begins when we acknowledge our base animal nature rather than aspiring to some airbrushed revolutionary ideal.

The cultural shockwaves of this porcine philosophy still reverberate through Chinese literature today. Younger writers describe reading Wang’s work as a physical experience—the text doesn’t just engage the mind but provokes visceral reactions. Some report actually retching at certain passages, not from disgust but from the sudden collapse of mental barriers between human dignity and animal reality. This isn’t magical realism; it’s biological realism that reduces all political posturing to its fecal essence.

Western readers often misinterpret Wang’s swine fixation as mere allegory. They miss the crucial point: his pigs aren’t symbols but flesh-and-blood creatures whose very existence mocks human pretensions. When Wang describes a boar’s testicles swinging like "two Marxist-Leninist pendulums" as the animal evades capture, he’s not crafting metaphor—he’s documenting a zoological fact that happens to devastate ideological certainty. This relentless conflation of the political and the porcine creates a new literary category: the scatological sublime.

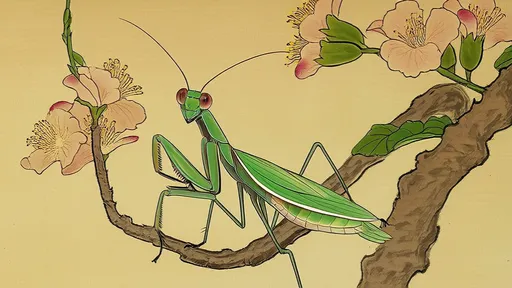

Contemporary censorship struggles to contain Wang’s legacy precisely because his rebellion operates on a cellular level. You can ban a political treatise, but how do you suppress a sentence comparing a young revolutionary’s ardor to a pig’s erection? The images burrow into the subconscious, breeding like… well, like pigs. Today’s Chinese youth invoke Wang not through direct quotation but through coded references to "the livestock section"—a nod to his uncanny ability to make human tyranny look absurd by viewing it through barnyard eyes.

The ultimate paradox of Wang’s swine philosophy lies in its theological implications. By reducing human struggle to animal compulsions, he accidentally elevates porcine existence to spiritual heights. His pigs don’t achieve Zen enlightenment—they achieve something rarer: perfect congruence between desire and action. In a society still wrestling with Wang’s legacy, perhaps true freedom still looks suspiciously like a contented hog sleeping in its own shit, blissfully unaware of any higher purpose.

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025