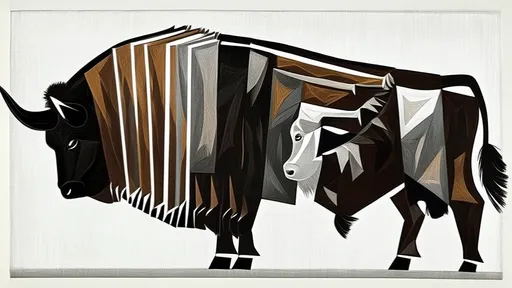

The story of Pablo Picasso's Bull series is more than an artistic exercise—it’s a profound meditation on the essence of form and meaning. Created in 1945, the eleven lithographs depict the gradual reduction of a bull from a detailed, anatomically accurate rendering to a few fluid lines that somehow still capture the animal’s spirit. This journey from complexity to simplicity reveals not just Picasso’s genius but also a deeper philosophical inquiry into what it means to perceive and represent reality.

Picasso began the series with a realistic depiction, almost academic in its precision. The first lithograph shows a heavy, muscular bull, its form shaded to emphasize volume and texture. It’s a bull as one might see it in life, grounded in the traditions of European art. Yet, with each subsequent stage, Picasso chipped away at the superfluous, stripping the bull down to its most elemental components. By the final lithograph, the bull is no more than a handful of curves and angles—a visual haiku that somehow feels more "bull-like" than the detailed original.

This process raises a compelling question: What is the minimum required to convey an idea? Picasso’s Bull suggests that truth isn’t found in accumulation but in distillation. The artist wasn’t just simplifying an image; he was engaging in a form of visual archaeology, digging through layers of assumption to uncover the primal essence beneath. In doing so, he challenged the viewer’s expectations of representation. A bull doesn’t need hooves or horns to be recognized—it needs only the right gesture, the right suggestion of force and movement.

The series also reflects a broader cultural shift in the early 20th century, where artists and thinkers were questioning the foundations of their disciplines. Just as Einstein reduced physics to energy and mass, or Joyce dismantled the novel’s structure, Picasso deconstructed the visual world. His Bull isn’t merely a stylistic experiment; it’s a manifesto for modernism, arguing that art’s power lies in its ability to evoke rather than replicate.

Yet there’s a paradox here. The final, most abstract bull is arguably the most "real" because it transcends literal representation. It exists in the mind as much as on the page, a collaboration between artist and viewer. This speaks to a fundamental truth about human perception: We don’t see with our eyes alone. We see with our memories, our associations, our unconscious sense of form. Picasso’s genius was in trusting that the viewer would meet him halfway, filling in the gaps with their own understanding of what a bull is.

The Bull series also invites us to consider the role of effort in art. The first lithograph required technical skill, but the last required something far rarer: the courage to erase. In a world that often equates complexity with value, Picasso’s reduction feels radical. It’s a reminder that mastery isn’t just about adding—it’s about knowing what to take away. This lesson extends beyond art. In design, science, even writing, the hardest work often isn’t creation but editing, the relentless pursuit of the irreducible core.

What makes the Bull timeless is its universality. Everyone understands simplification, whether they’ve struggled to pack a suitcase or summarize a complex idea. Picasso’s series mirrors the way memory works, how we condense experiences into symbols over time. The bull becomes a metaphor for how we process the world—how we, too, distill the chaotic detail of life into patterns and essences that we can carry with us.

Ultimately, the Bull isn’t about bulls at all. It’s about the act of seeing, the space between reality and perception. Picasso’s eleven stages are a visual koan, a puzzle that resists easy answers. The more you look, the more you realize that simplicity isn’t the opposite of complexity—it’s complexity understood so thoroughly that it can be expressed with a single, unbroken line.

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025

By /Jul 24, 2025